The Fire of Rome, by

Karl von Piloty, 1861. According to Tacitus, Nero targeted

Christians as those responsible for the fire.

Scholars generally consider Tacitus's reference to the execution of Jesus by

Pontius Pilate to be both authentic, and of historical value as an independent Roman source.

[5][6][7] Eddy and Boyd state that it is now "firmly established" that Tacitus provides a non-Christian confirmation of the

crucifixion of Jesus.

[8] However, there have been suggestions that the 'Christ, the author of this name, was executed by the procurator Pontius Pilate in the reign of Tiberius' line is a Christian interpolation.

[9][10]

Historian

Ronald Mellor has stated that the

Annals is "Tacitus's crowning achievement" which represents the "pinnacle of Roman historical writing".

[11] Scholars view it as establishing three separate facts about Rome around AD 60: (i) that there were a sizable number of Christians in Rome at the time, (ii) that it was possible to distinguish between Christians and Jews in Rome, and (iii) that at the time pagans made a connection between Christianity in Rome and its origin in

Roman Judea.

[12][13] These facts however are so narrowly established (see

Other Roman Sources below) that they are subject to much scrutiny, like reports of Pilate's rank or the spelling of key words or Tacitus' actual sources.

The passage and its context[edit]

A copy of the second Medicean manuscript of

Annals,

Book 15, chapter 44, the page with the reference to Christians

The

Annals passage (

15.44), which has been subjected to much scholarly analysis, follows a description of the six-day

Great Fire of Rome that burned much of Rome in July 64 AD.

[3]

"Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind".

(In Latin:

[2] ergo abolendo rumori Nero subdidit reos et quaesitissimis poenis adfecit, quos per flagitia invisos vulgus Chrestianos appellabat. auctor nominis eius Christus Tibero imperitante per procuratorem Pontium Pilatum supplicio adfectus erat; repressaque in praesens exitiablilis superstitio rursum erumpebat, non modo per Iudaeam, originem eius mali, sed per urbem etiam, quo cuncta undique atrocia aut pudenda confluunt celebranturque. igitur primum correpti qui fatebantur, deinde indicio eorum multitudo ingens haud proinde in crimine incendii quam odio humani generis convicti sunt.)

Tacitus then describes the torture of Christians. The exact cause of the fire remains uncertain, but much of the population of Rome suspected that

Emperor Nero had started the fire himself.

[3] To divert attention from himself, Nero accused the Christians of starting the fire and persecuted them, making this the first confrontation between Christians and the authorities in Rome.

[3] Tacitus never accused Nero of playing the

lyre while Rome burned - that statement came from

Cassius Dio, who died in the 3rd century.

[2] But Tacitus did suggest that Nero used the Christians as scapegoats.

[14]

No original manuscripts of the

Annals exist and the surviving copies of Tacitus' works derive from two principal manuscripts, known as the

Medicean manuscripts, written in

Latin, which are held in the

Laurentian Library in

Florence, Italy.

[15] It is the

second Medicean manuscript, 11th century and from the

Benedictine abbey at

Monte Cassino, which is the oldest surviving copy of the passage describing Christians.

[16] Scholars generally agree that these copies were written at Monte Cassino and the end of the document refers to

Abbas Raynaldus cu... who was most probably one of the two abbots of that name at the abbey during that period.

[16]

Specific references[edit]

Christians and Chrestians[edit]

Detail of the 11th century copy of Annals, the gap between the 'i' and 's' is highlighted in the word 'Christianos'.

The passage states:

- "... called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin ..."

In 1902 Georg Andresen commented on the appearance of the first 'i' and subsequent gap in the earliest extant, 11th century, copy of the Annals in

Florence, suggesting that the text had been altered, and an 'e' had originally been in the text, rather than this 'i'.

[17] "With ultra-violet examination of the MS the alteration was conclusively shown. It is impossible today to say who altered the letter

e into an

i. In Suetonius’

Nero 16.2, "christiani", however, seems to be the original reading".

[18] Since the alteration became known it has given rise to debates among scholars as to whether Tacitus deliberately used the term "Chrestians", or if a scribe made an error during the

Middle Ages.

[19][20] It has been stated that both the terms Christians and Chrestians had at times been used by the general population in Rome to refer to early Christians.

[21] Robert Van Voorst states that many sources indicate that the term Chrestians was also used among the early followers of Jesus by the second century.

[20][22] The term Christians appears only three times in the

New Testament, the first usage (

Acts 11:26) giving the origin of the term.

[20] In all three cases the uncorrected

Codex Sinaiticus in Greek reads

Chrestianoi.

[20][22] In

Phrygia a number of funerary stone inscriptions use the term Chrestians, with one stone inscription using both terms together, reading: "

Chrestians for Christians".

[22]

Adolf von Harnack argued that Chrestians was the original wording, and that Tacitus deliberately used

Christus immediately after it to show his own superior knowledge compared to the population at large.

[20] Robert Renehan has stated that it was natural for a Roman to mix the two words that sounded the same, that Chrestianos was the original word in the Annals and not an error by a scribe.

[23][24] Van Voorst has stated that it was unlikely for Tacitus himself to refer to Christians as Chrestianos i.e. "useful ones" given that he also referred to them as "hated for their shameful acts".

[19] Paul Eddy sees no major impact on the authenticity of the passage or its meaning regardless of the use of either term by Tacitus.

[25]

The rank of Pilate[edit]

Pilate's rank while he was governor of

Iudaea province appeared in a Latin inscription on the

Pilate Stone which called him a

prefect, while this Tacitean passage calls him a

procurator.

Josephus refers to Pilate with the generic Greek term

ἡγεμών,

hēgemōn, or governor. Tacitus records that

Claudius was the ruler who gave procurators governing power.

[26][27] After

Herod Agrippa's death in AD 44, when Judea reverted to direct Roman rule, Claudius gave procurators control over Judea.

[3][28][29][30]

Various theories have been put forward to explain why Tacitus should use the term "procurator" when the archaeological evidence indicates that Pilate was a prefect. Jerry Vardaman theorizes that Pilate's title was changed during his stay in Judea and that the Pilate Stone dates from the early years of his administration.

[31] Baruch Lifshitz postulates that the inscription would originally have mentioned the title of "procurator" along with "prefect".

[32] L.A. Yelnitsky argues that the use of "procurator" in Annals 15.44.3 is a Christian interpolation.

[33] S.G.F. Brandon suggests that there is no real difference between the two ranks.

[34] John Dominic Crossan states that Tacitus "retrojected" the title procurator which was in use at the time of

Claudius back onto Pilate who was called prefect in his own time.

[35] Bruce Chilton and

Craig Evans as well as Van Voorst state that Tacitus apparently used the title

procurator because it was more common at the time of his writing and that this variation in the use of the title should not be taken as evidence to doubt the correctness of the information Tacitus provides.

[36][37]Warren Carter states that, as the term "prefect" has a military connotation, while "procurator" is civilian, the use of either term may be appropriate for governors who have a range of military, administrative and fiscal responsibilities.

[38]

Louis Feldman says that

Philo (who died AD 50) and

Josephus also use the term procurator for Pilate.

[39] It should be noted that, as both Philo and Josephus wrote in Greek, neither of them actually used the term "procurator", but the Greek word

ἐπίτροπος (

epitropos), which is regularly translated as "procurator". Philo also uses this Greek term for the governors of

Egypt (a prefect), of

Asia (a proconsul) and

Syria (a legate).

[40] Werner Eck, in his list of terms for governors of Judea found in the works of Josephus, shows that, while in the early work,

The Jewish War, Josephus uses

epitropos less consistently, the first governor to be referred to by the term in

Antiquities of the Jews was

Cuspius Fadus, (who was in office AD 44-46).

[41] Feldman notes that Philo, Josephus and Tacitus may have anachronistically confused the timing of the titles - prefect later changing to procurator.

[39] Feldman also notes that the use of the titles may not have been rigid, for Josephus refers to Cuspius Fadus both as "prefect" and "procurator".

[39]

Authenticity and historical value[edit]

The title page of 1598 edition of the works of Tacitus, kept in

Empoli,

Italy.

Most modern scholars consider the passage to be authentic.

[42][43] William L. Portier has stated that the consistency in the references by Tacitus, Josephus and the letters to

Emperor Trajan by

Pliny the Younger reaffirm the validity of all three accounts.

[43] Scholars generally consider Tacitus's reference to be of historical value as an independent Roman source about early Christianity that is in unison with other historical records.

[5][6][7][43]

Tacitus was a patriotic

Roman senator.

[44][45] His writings shows no sympathy towards Christians, or knowledge of who their leader was.

[5][46]His characterization of "Christian abominations" may have been based on the rumors in Rome that during the

Eucharist rituals Christians ate the body and drank the blood of their God, interpreting the ritual as cannibalism by Christians.

[46][47] Andreas Köstenberger states that the tone of the passage towards Christians is far too negative to have been authored by a Christian scribe.

[48] Van Voorst also states that the passage is unlikely to be a Christian forgery because of the pejorative language used to describe Christianity.

[42]

Tacitus was about 7 years old at the time of the

Great Fire of Rome, and like other Romans as he grew up he would have most likely heard about the fire that destroyed most of the city, and Nero's accusations against Christians.

[14] When he wrote his account, Tacitus was the governor of the province of Asia, and as a member of the inner circle in Rome he would have known of the official position with respect to the fire and the Christians.

[14]

In 1885 P. Hochart had proposed that the passage was a

pious fraud,

[49] but the editor of the 1907 Oxford edition dismissed his suggestion and treated the passage as genuine.

[50] Scholars such as Bruce Chilton,

Craig Evans, Paul R. Eddy and Gregory A. Boyd agree with John Meier's statement that "Despite some feeble attempts to show that this text is a Christian interpolation in Tacitus, the passage is obviously genuine.”

[36][51] However in 2014 an article by Richard Carrier detailing the reasons to suspect the "Their founder, one Christ, had been put to death by the procurator, Pontius Pilate in the reign of Tiberius" part in the passage is a Christian interpolation was published in

Vigiliae Christianae[52] some of which are highlighted in Carrier's

On the Historicity of Jesus where he also presents reasons that even if it is totally genuine there are reasons to suspect Tacitus is merely repeating a story told by the Christians themselves.

[53] Suggestions that the whole of Annals may have been a forgery have also been generally rejected by scholars.

[54]

John P. Meier states that there is no historical or archaeological evidence to support the argument that a scribe may have introduced the passage into the text.

[55]

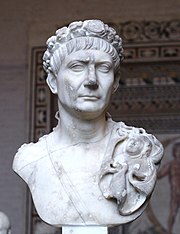

Portrait of Tacitus, based on an antique bust.

Van Voorst states that "of all Roman writers, Tacitus gives us the most precise information about Christ".

[42] John Dominic Crossan considers the passage important in establishing that Jesus existed and was crucified, and states: "That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus... agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact."

[56] Eddy and Boyd state that it is now "firmly established" that Tacitus provides a non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus.

[8] Biblical scholar

Bart D. Ehrman wrote: "Tacitus's report confirms what we know from other sources, that Jesus was executed by order of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, sometime during Tiberius's reign."

[57]

James D. G. Dunn considers the passage as useful in establishing facts about

early Christians, e.g. that there was a sizable number of Christians in Rome around AD 60.

[12] Dunn states that Tacitus seems to be under the impression that Christians were some form of Judaism, although distinguished from them.

[12] Raymond E. Brown and

John P. Meier state that in addition to establishing that there was a large body of Christians in Rome, the Tacitus passage provides two other important pieces of historical information, namely that by around AD 60 it was possible to distinguish between Christians and Jews in Rome and that even pagans made a connection between Christianity in Rome and its origin in Judea.

[13]

Although the majority of scholars consider it to be genuine, a few scholars question the authenticity of the passage given that Tacitus was born 25 years after Jesus' death.

[42]

Some scholars have debated the historical value of the passage given that Tacitus does not reveal the source of his information.

[58] Gerd Theissen and Annette Merz argue that Tacitus at times had drawn on earlier historical works now lost to us, and he may have used official sources from a Roman archive in this case; however, if Tacitus had been copying from an official source, some scholars would expect him to have labeled Pilate correctly as a

prefect rather than a

procurator.

[59]Theissen and Merz state that Tacitus gives us a description of widespread prejudices about Christianity and a few precise details about "Christus" and Christianity, the source of which remains unclear.

[60] However, Paul R. Eddy has stated that given his position as a senator Tacitus was also likely to have had access to official Roman documents of the time and did not need other sources.

[25]

Michael Martin notes that the authenticity of this passage of the Annals has also been disputed on the grounds that Tacitus would not have used the word “messiah” in an authentic Roman document.

[61]

Weaver notes that Tacitus spoke of the persecution of Christians, but no other Christian author wrote of this persecution for a hundred years.

[62]

Hotema notes that this passage was not quoted by any Church father up to the 15th century, although the passage would have been very useful to them in their work;

[63] and that the passage refers to the Christians in Rome being a multitude, while at that time the Christian congregation in Rome would actually have been very small.

[64]

Scholars have also debated the issue of hearsay in the reference by Tacitus. Charles Guignebert argued that "So long as there is that possibility [that Tacitus is merely echoing what Christians themselves were saying], the passage remains quite worthless".

[65] R. T. France states that the Tacitus passage is at best just Tacitus repeating what he had heard through Christians.

[66] However, Paul R. Eddy has stated that as Rome's preeminent historian, Tacitus was generally known for checking his sources and was not in the habit of reporting gossip.

[25] Tacitus was a member of the

Quindecimviri sacris faciundis, a council of priests whose duty it was to supervise foreign religious cults in Rome, which as Van Voorst points out, makes it reasonable to suppose that he would have acquired knowledge of Christian origins through his work with that body.

[67]

Other Roman sources[edit]

See also[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|

References[edit]

- Jump up^ P.E. Easterling, E. J. Kenney (general editors), The Cambridge History of Latin Literature, page 892 (Cambridge University Press, 1982, reprinted 1996). ISBN 0-521-21043-7

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stephen Dando-Collins 2010 The Great Fire of Rome ISBN 978-0-306-81890-5pages 1-4

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e A political history of early Christianity by Allen Brent 2009 ISBN 0-567-03175-6pages 32-34

- Jump up^ Robert Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000. p 39- 53

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies by Craig A. Evans 2001 ISBN 0-391-04118-5 page 42

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 2001 ISBN 0-86554-373-9 page 343

- ^ Jump up to:a b Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation by Helen K. Bond 2004 ISBN 0-521-61620-4 page xi

- ^ Jump up to:a b Eddy, Paul; Boyd, Gregory (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition Baker Academic, ISBN 0-8010-3114-1 page 127

- Jump up^ Carrier, Richard (2014) "The Prospect of a Christian Interpolation in Tacitus, Annals 15.44" Vigiliae Christianae, Volume 68, Issue 3, pages 264 – 283 (an earlier and more detailed version appears in Carrier's Hitler Homer Bible Christ)

- Jump up^ Carrier, Richard (2014) On the Historicity of Jesus Sheffield Phoenix Press ISBN 978-1-909697-49-2 pg 344

- Jump up^ Tacitus' Annals by Ronald Mellor 2010 ISBN 0-19-515192-5 Oxford page 23

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Beginning from Jerusalem by James D. G. Dunn 2008 ISBN 0-8028-3932-0 pages 56-57

- ^ Jump up to:a b Antioch and Rome: New Testament cradles of Catholic Christianity by Raymond Edward Brown, John P. Meier 1983 ISBN 0-8091-2532-3 page 99

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times by Paul Barnett 2002 ISBN 0-8308-2699-8 page 30

- Jump up^ Cornelii Taciti Annalium, Libri V, VI, XI, XII: With Introduction and Notes by Henry Furneaux, H. Pitman 2010 ISBN 1-108-01239-6 page iv

- ^ Jump up to:a b Newton, Francis, The Scriptorium and Library at Monte Cassino, 1058–1105, ISBN 0-521-58395-0 Cambridge University Press, 1999. "The Date of the Medicean Tacitus (Flor. Laur. 68.2)", p. 96-97. [1]

- Jump up^ Georg Andresen in Wochenschrift fur klassische Philologie 19, 1902, col. 780f

- Jump up^ J. Boman, Inpulsore Cherestro? Suetonius’ Divus Claudius 25.4 in Sources and Manuscripts, Liber Annuus 61 (2011), ISSN 0081-8933, Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem 2012, p. 355, n. 2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Van Voorst, Robert E (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence Eerdmans Publishing ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 pages 44-48

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A-D by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1995ISBN 0-8028-3781-6 page 657

- Jump up^ Christians at Rome in the First Two Centuries by Peter Lampe 2006 ISBN 0-8264-8102-7 page 12

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Van Voorst, Robert E (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence Eerdmans Publishing ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 pages 33-35

- Jump up^ Robert Renehan, "Christus or Chrestus in Tacitus?", La Parola del Passato 122 (1968), pp. 368-370

- Jump up^ Transactions and proceedings of the American Philological Association, Volume 29, JSTOR (Organization), 2007. p vii

- ^ Jump up to:a b c The Jesus legend: a case for the historical reliability of the synoptic gospels by Paul R. Eddy, et al 2007 ISBN 0-8010-3114-1 pages 181-183

- Jump up^ Tacitus, Annals 12.60: Claudius said that the judgments of his procurators had the same efficacy as those judgments he made.

- Jump up^ P. A. Brunt, Roman imperial themes, Oxford University Press, 1990, ISBN 0-19-814476-8, ISBN 978-0-19-814476-2. p.167.

- Jump up^ Tacitus, Histories 5.9.8.

- Jump up^ Geoffrey W. Bromiley, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1988. ISBN 0-8028-3785-9, ISBN 978-0-8028-3785-1. p.979, col.1.

- Jump up^ Paul, apostle of the heart set free by F. F. Bruce (2000) ISBN 1842270273 Eerdsmans page 354

- Jump up^ "A New Inscription Which Mentions Pilate as 'Prefect'", JBL 81/1 (1962), p.71.

- Jump up^ "Inscriptions latines de Cesaree (Caesarea Palaestinae)" in Latomus 22 (1963), pp.783-784.

- Jump up^ "The Caesarea Inscription of Pontius Pilate and Its Historical Significance" in Vestnik Drevnej Istorii 93 (1965), pp.142-146.

- Jump up^ "Pontius Pilate in history and legend" in History Today 18 (1968), pp. 523—530

- Jump up^ Birth of Christianity by John Dominic Crossan (Apr 1, 1999) ISBN 0567086682 T & T Clark p.9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Studying the historical Jesus: evaluations of the state of current research by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998 ISBN 90-04-11142-5 pages 465-466

- Jump up^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000. p.48.

- Jump up^ Pontius Pilate: Portraits of a Roman Governor by Warren Carter (Sep 1, 2003) ISBN 0814651135 page 44

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Louis Feldman "Flavius Josephus Revisited" in Aufstieg Und Niedergang Der Roemischen Welt, Part 2 edited by Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase 1984 ISBN 311009522X page 818

- Jump up^ Matthew and Empire: Initial Explorations by Warren Carter (T&T Clark: October 10, 2001) ISBN 978-1563383427 p.215.

- Jump up^ Werner Eck, "Die Benennung von römischen Amtsträgern und politisch-militärisch-administrativenFunktionen bei Flavius Iosephus: Probleme der korrekten IdentifizierungAuthor" in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 166 (2008), p.222.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000. p 39- 53

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Tradition and Incarnation: Foundations of Christian Theology by William L. Portier 1993 ISBN 0-8091-3467-5 page 263

- Jump up^ Josephus, the Bible, and history by Louis H. Feldman 1997 ISBN 90-04-08931-4 page 381

- Jump up^ Jesus as a figure in history: how modern historians view the man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell 1998 ISBN 0-664-25703-8 page 33

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ancient Rome by William E. Dunstan 2010 ISBN 0-7425-6833-4 page 293

- Jump up^ An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity by Delbert Royce Burkett 2002 ISBN 0-521-00720-8 page 485

- Jump up^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pages 109-110

- Jump up^ Henry Furneaux, ed., Cornelii Taciti Annalium ab excessu divi augusti libri. The annals of Tacitus with introduction and notes, 2nd ed., vol. ii, books xi-xvi. Clarendon, 1907. Appendix II, p. 416f."

- Jump up^ Henry Furneaux, ed., Cornelii Taciti Annalium ab excessu divi augusti libri. The annals of Tacitus with introduction and notes, 2nd ed., vol. ii, books xi-xvi. Clarendon, 1907. Appendix II, p.418

- Jump up^ The Jesus Legend: a case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition by Paul R. Eddy, Gregory A. Boyd 2007 ISBN 0-8010-3114-1 page 181

- Jump up^ Carrier, Richard (2014) "The Prospect of a Christian Interpolation in Tacitus, Annals 15.44" Vigiliae Christianae, Volume 68, Issue 3, pages 264 – 283 (an earlier and more detailed version appears in Carrier's Hitler Homer Bible Christ)

- Jump up^ Carrier, Richard (2014) On the Historicity of Jesus Sheffield Phoenix Press ISBN 978-1-909697-49-2 pg 343-346

- Jump up^ Robert Van Voorst Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence 2000 ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 page 42

- Jump up^ Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Doubleday: 1991. vol 1: p. 168-171.

- Jump up^ Crossan, John Dominic (1995). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperOne. ISBN 0-06-061662-8 page 145

- Jump up^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2001). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0195124743.

- Jump up^ F.F. Bruce,Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974) p. 23

- Jump up^ Theissen and Merz p.83

- Jump up^ Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998). The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8006-3122-2.

- Jump up^ The Case Against Christianity, By Michael Martin, pg 50-51, athttp://books.google.co.za/books?id=wWkC4dTmK0AC&pg=PA52&dq=historicity+of+jesus&hl=en&sa=X&ei=o-_8U5-yEtTH7AbBpoCoAg&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=tacitus&f=false

- Jump up^ The Historical Jesus in the Twentieth Century: 1900-1950, By Walter P. Weaver, pg 53, pg 57, at http://books.google.co.za/books?id=1CZbuFBdAMUC&pg=PA45&dq=historicity+of+jesus&hl=en&sa=X&ei=o-_8U5-yEtTH7AbBpoCoAg&ved=0CEoQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=tacitus&f=false

- Jump up^ Secret of Regeneration, By Hilton Hotema, pg 100, at http://books.google.co.za/books?id=jCaopp3R5B0C&pg=PA100&dq=interpolations+in+tacitus&hl=en&sa=X&ei=CRf-U9-VGZCe7AbxrIDQCA&ved=0CCAQ6AEwATge#v=onepage&q=interpolations%20in%20tacitus&f=false

- Jump up^ Secret of Regeneration, By Hilton Hotema, pg 100, at http://books.google.co.za/books?id=jCaopp3R5B0C&pg=PA100&dq=interpolations+in+tacitus&hl=en&sa=X&ei=CRf-U9-VGZCe7AbxrIDQCA&ved=0CCAQ6AEwATge#v=onepage&q=interpolations%20in%20tacitus&f=false

- Jump up^ Jesus, University Books, New York, 1956, p.13

- Jump up^ France, RT (1986). Evidence for Jesus (Jesus Library). Trafalgar Square Publishing. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-340-38172-8.

- Jump up^ Van Voorst, Robert E. (2011). Handbook for the Study of the Historical Jesus. Brill Academic Pub. p. 2159. ISBN 978-9004163720.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Stephen Benko "Pagan Criticism of Christianity" in Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt edited by Hildegard Temporin et al ISBN 3110080168 page

- Jump up^ Robert E. Van Voorst Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 page 69-70

- Jump up^ Christianity and the Roman Empire: background texts by Ralph Martin Novak 2001 ISBN 1-56338-347-0 pages 13 and 20

No comments:

Post a Comment