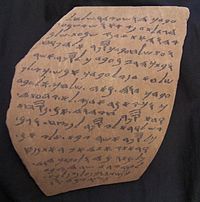

This amazing discovery in January–February, 1935, by James Leslie Starkey, written in carbon ink in Ancient Hebrew on clay ostraca, reveals the divine name of Yahweh (Lord) and was written when the babylonian army went forward to Jerusalem in the time of Zedekiah, the biblical character, the last king of Judah before the destruction of the kingdom by Babylon.

To my lord, Yaush, may YHWH cause my lord to hear tiding(s) of peace today, this very day! Who is your servant, a dog, that my lord remembered his [se]rvant? May YHWH make known(?) to my [lor]d a matter of which you do not know.

There are scriptures which reference what is written on, The Lachish Letters or Lachish Ostrak.

English Standard Version

when the army of the king of Babylon was fighting against Jerusalem and against all the cities of Judah that were left, Lachish and Azekah, for these were the only fortified cities of Judah that remained. Jeremiah 34:7.

English Standard Version

And he paid homage and said, “What is your servant, that you should show regard for a dead dog such as I?” 2 Samuel 9:8.

English Standard Version

Then Abishai the son of Zeruiah said to the king, “Why should this dead dog curse my lord the king? Let me go over and take off his head.” 2 Samuel 16:9.

English Standard Version

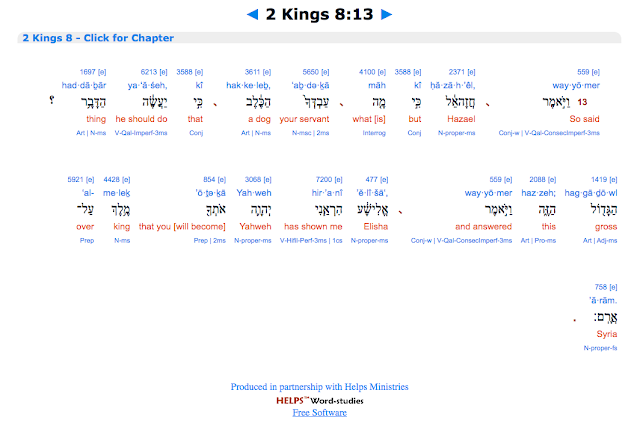

And Hazael said, “What is your servant, who is but a dog, that he should do this great thing?” Elisha answered, “The LORD has shown me that you are to be king over Syria.” 2 Kings 8:13.

World English Bible

Hazael said, "But what is your servant, who is but a dog, that he should do this great thing?" Elisha answered, "Yahweh has shown me that you will be king over Syria."

RELATED ARTICLES.

Links and much more info from the Wikipedia site, the free encyclopedia.

Lachish letters

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lachish letter III replica (front side)

| |

| Material | Clay ostraca |

|---|---|

| Writing | Phoenician script / Paleo-Hebrew script |

| Created | c. 590 BC |

| Discovered | 1935 |

| Present location | British Museum and Israel Museum |

| Identification | ME 125701 to ME 125707, ME 125715a, IAA 1938.127 and 1938.128 |

The Lachish Letters or Lachish Ostraka, sometimes called Hoshaiah Letters, are a series of letters written in carbon ink in Ancient Hebrew on clay ostraca. The letters were discovered at the excavations at Lachish(Tell ed-Duweir).

The ostraka were discovered by James Leslie Starkey in January–February, 1935 during the third campaign of the Wellcome excavations. They were published in 1938 by Harry Torczyner (name later changed to Naftali Herz Tur-Sinai) and have been much studied since then. Seventeen of them are currently located in the British Museum in London,[1] a smaller number (including Letter 6) are on permanent display at the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem, Israel.[2]

Contents

[hide]Interpretation[edit]

The individual ostraca probably come from the same broken clay pot and were most likely written in a short period of time. They were written to Yaush (or Ya'osh), possibly the commanding officer at Lachish, from Hoshaiah (Hoshayahu), a military officer stationed in a city close to Lachish (possibly Mareshah). In the letters, Hoshaiah defends himself to Yaush regarding a letter he either was or was not supposed to have read. The letters also contain informational reports and requests from Hoshaiah to his superior. The letters were probably written shortly before Lachish fell to the Babylonian army of King Nebuchadnezzar in 588/6 BC during the reign of Zedekiah, king of Judah (ref. Jeremiah 34:7).

Text of the Letters[edit]

- Letter Number 2

To my lord, Yaush, may YHWH cause my lord to hear tiding(s) of peace today, this very day! Who is your servant, a dog, that my lord remembered his [se]rvant? May YHWH make known(?) to my [lor]d a matter of which you do not know.[3]

- Letter Number 3

Your servant, Hoshayahu, sent to inform my lord, Yaush: May YHWH cause my lord to hear tidings of peace and tidings of good. And now, open the ear of your servant concerning the letter which you sent to your servant last evening because the heart of your servant is ill since your sending it to your servant. And inasmuch as my lord said "Don't you know how to read a letter?" As YHWH lives if anyone has ever tried to read me a letter! And as for every letter that comes to me, if I read it. And furthermore, I will grant it as nothing. And to your servant it has been reported saying: The commander of the army Konyahu son of Elnatan, has gone down to go to Egypt and he sent to commandeer Hodawyahu son of Ahiyahu and his men from here. And as for the letter of Tobiyahu, the servant of the king, which came to Sallum, the son of Yaddua, from the prophet, saying, "Be on guard!" your ser[va]nt is sending it to my lord.[4]

Notes: This ostracon is approximately fifteen centimeters tall by eleven centimeters wide and contains twenty-one lines of writing. The front side has lines one through sixteen; the back side has lines seventeen through twenty-one. This ostracon is particularly interesting because of its mentions of Konyahu, who has gone down to Egypt, and the prophet. For possible biblical connections according to Torczyner, reference Jeremiah 26:20-23.

- Letter Number 4

May YHW[H] cause my [lord] to hear, this very day, tidings of good. And now, according to everything which my lord has sent, this has your servant done. I wrote on the sheet according to everything which [you] sent [t]o me. And inasmuch as my lord sent to me concerning the matter of Bet Harapid, there is no one there. And as for Semakyahu, Semayahu took him and brought him up to the city. And your servant is not sending him there any[more ---], but when morning comes round [---]. And may (my lord) be apprised that we are watching for the fire signals of Lachish according to all the signs which my lord has given, because we cannot see Azeqah.[5]

- Letter Number 5

May YHWH cause my [lo]rd to hear tidings of pea[ce] and of good, [now today, now this very da]y! Who is your servant, a dog, that you [s]ent your servant the [letters? Like]wise has your servant returned the letters to my lord. May YHWH cause you to see the harvest successfully, this very day! Will Tobiyahu of the royal family c<o>me to your servant?[6]

- Letter Number 6

To my lord, Yaush, may YHWH cause my lord to see peace at this time! Who is your servant, a dog, that my lord sent him the king's [lette]r [and] the letters of the officer[s, sayin]g, "Please read!" And behold, the words of the [officers] are not good; to weaken your hands [and to in]hibit the hands of the m[en]. [I(?)] know [them(?)]. My lord, will you not write to [them] sa[ying, "Wh]y are you behaving this way? [ . . . ] well-being [ . . . ]. Does the king [ . . . ] And [ . . . ] As YHWH lives, since your servant read the letters, your servant has not had [peace(?)].[7]

- Letter Number 9

May YHWH cause my lord to hear ti[dings] of peace and of [good. And n]ow, give 10 (loaves) of bread and 2 (jars) [of wi]ne. Send back word [to] your servant by means of Selemyahu as to what we must do tomorrow. [8]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ Lakhish Ostraca, c. 587 BCE

- ^ Translation from Aḥituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past. Jerusalem: CARTA Jerusalem, 2008, pg. 60.

- ^ Translation from Aḥituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past. Jerusalem: CARTA Jerusalem, 2008, pg. 63.

- ^ Translation from Aḥituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past. Jerusalem: CARTA Jerusalem, 2008, pg. 70.

- ^ Translation from Aḥituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past. Jerusalem: CARTA Jerusalem, 2008, pg. 77.

- ^ Translation from Aḥituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past. Jerusalem: CARTA Jerusalem, 2008, pg. 80.

- ^ Translation from Aḥituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past. Jerusalem: CARTA Jerusalem, 2008, pg. 85.

External links[edit]

Further reading[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lachish letters. |

- Torczyner, Harry. Lachish I: The Lachish Letters. London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1938.

- Lemaire, A. Inscriptions Hebraiques I: Les ostraca (Paris, Cerf, 1977).

- Rainey, A.F. "Watching for the Signal Fires of Lachis," PEQ 119 (1987), pp. 149–151.

- Lachish ostraca at the British Museum [1]

Tel Lachish

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the ancient town. For other uses, see Lakhish (disambiguation).

This article is about Tell ed-Duweir or Lachish in the Shfela. For Khirbet ed-Duweir in Jordan Valley, see Lo-debar.

| תל לכיש (Hebrew) | |

Main gate of Lachish

| |

| Location | Southern District, Israel |

|---|---|

| Region | Shephelah |

| Coordinates | 31°33′54″N 34°50′56″ECoordinates: 31°33′54″N 34°50′56″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 20 ha (49 acres) |

| History | |

| Abandoned | 587 BCE |

| Events | Siege of Lachish (701 BCE) |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1932–1938, 1966, 1968, 1973–1994 |

| Archaeologists | James Leslie Starkey, Olga Tuffnell, Yohanan Aharoni, David Ussishkin |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

Tel Lachish (Hebrew: תל לכיש; Greek: Λαχις; Latin: Tel Lachis), also Tell ed-Duweir, is the site of an ancient Near East city, now an archaeological site and an Israeli national park. Lachish is located in the Shephelah region of Israel between Mount Hebron and the Mediterranean coast. It is first mentioned in the Amarna letters asLakisha-Lakiša (EA 287, 288, 328, 329, 335). According to the Bible, the Israelites captured and destroyed Lachish for joining the league against the Gibeonites(Joshua 10:31-33). The territory was later assigned to the tribe of Judah (15:39) and became part of the Kingdom of Israel.

Of the cities in ancient Judah, Lachish was second in importance only to Jerusalem.[1] One of the Lachish letters warns of the impending Babylonian destruction. It reads: "Let my lord know that we are watching over the beacon of Lachish, according to the signals which my lord gave, for Azekah is not seen." According to the prophet Jeremiah, Lachish and Azekah were the last two Judean cities before the conquest of Jerusalem (Jer. 34:7). This pottery inscription can be seen at theIsrael Museum in Jerusalem.[2]

Contents

[hide]History[edit]

Occupation at the site of Lachish began during the Pottery Neolithic period (5500–4500 BCE). Major development began in the Early Bronze Age (3300–3000 BCE).[1] During the Middle Bronze II (2000–1650 BCE), the Canaanite settlement came under strong Egyptian influence. The next peak was the late Late Bronze Age (1650–1200 BCE), when Lachish is mentioned in the Amarna letters. This phase of the city was destroyed in a fire ca. 1150 BCE. The city, under protection of the New Kingdom of Egypt, was rebuilt by the Caananites. One of the two discovered temples was built at the northwest corner of the mound, outside the city limits and within the disused moat, which led the archaeologists to call it the Fosse Temple. However, this settlement was soon destroyed by another fire, perhaps from an invasion by the Sea Peoples or Israelites. The mound was abandoned for two centuries.[1]

Rebuilding of the city began in the Early Iron Age during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE when it was settled by the Israelites. The unfortified settlement may have been destroyed c. 925 BCE by Egyptian Pharaoh Sheshonk I.[1] In the first half of the 9th century BCE, under the kings Asa and Jehoshaphat, Lachish became an important city in the kingdom of Judah. It was heavily fortified with massive walls and ramparts and a royal palace was built on a platform in the center of the city.[1]Lachish was the foremost among several fortified cities and strongholds guarding the valleys that lead up to Jerusalem and the interior of the country against enemies which usually approached from the coast.

In 701 BCE, during the revolt of king Hezekiah against Assyria, it was besieged and captured by Sennacherib despite the defenders' determined resistance.[3] Some scholars believe that the fall of Lachish actually occurred during a second campaign in the area by Sennacherib ca. 688 BCE.[citation needed] The site now contains the only remains of an Assyrian siege ramp discovered so far. Sennacherib later devoted a whole room in his "Palace without a rival", the South-west palace inNineveh, for artistic representations of the siege on large alabaster slabs, most of which are now on display in the British Museum. They hold depictions of Assyrian siege ramps, battering rams, sappers, and other siege machines and army units, along with Lachish's architecture and its final surrender. In combination with the archaeological finds, they give a good understanding of siege warfare of the period.[4] So much attention was given to the success at Lachish also because, unlike it, Jerusalem managed to withstand Sennacherib's onslaught.

The town was rebuilt in the late 7th century BCE during the decline of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. However, the city fell to Nebuchadnezzar in his campaign against Judah in 586 BCE.

Modern excavation of the site has revealed that the Assyrians built a stone and dirt ramp up to the level of the Lachish city wall, thereby allowing the soldiers to charge up the ramp and storm the city. Excavations revealed approximately 1,500 skulls in one of the caves near the site, and hundreds of arrowheads on the ramp and at the top of the city wall, indicating the ferocity of the battle. The city occupied an area of 8 hectares (20 acres) and was finally destroyed in 587 BCE.[5] Residents were exiled as part of theBabylonian captivity.[1]

During Babylonian occupation, a large residence was built on the platform that had once supported the Israeli palace. At the end of the captivity, some exiled Jews returned to Lachish and built a new city with fortifications. Under the Babylonian or Achaemenid Empire, a large altar (known as the Solar Shrine) on the east section of the mound was built. The shrine was abandoned after the area fell in the hands of Alexander the Great. The tell has been unoccupied since then.[1]

Biblical references[edit]

Lachish is mentioned in several books in the Hebrew Bible. The Book of Joshua refers to Lachish in chapter 10 (verses 3, 5, 23, and 31-35), describing the Israelite conquest of Caanan. Japhia, the King of Lachish, is listed as one of the Five Amorite Kings that allied to repel the invasion. After a surprise attack from the Israelites, the kings took refuge in a cave, where they were captured and put to death. Joshua and the Israelites then took the city of Lachish after a two-day siege, exterminating the populace. In 12:11, the King of Lachish is mentioned as one of the thirty-one kings conquered by Joshua. The city is assigned to the Tribe of Judah in 15:39 as part of the western foothills.

Rehoboam's fortifications of Lachish are recorded in II Chronicles (11:9). In II Kings (14:17) and II Chronicles 25:27, Amaziah of Judah flees to Lachish after he was defeated by Jehoash of Israel, where he is captured and executed.

The Book of Micah (1:13) warns the residents of Lachish that the destruction of Samaria by the Assyrians will soon spread to Judah. Chapter 18, verse 14 of II Kings mentions the Siege of Lachish; Hezekiah sends a message there offering tribute to Sennacherib in exchange for the city. In verse 17, the Assyrians leave Lachish and head to Jerusalem to begin the unsuccessful Assyrian Siege of Jerusalem. This is also mentioned in II Chronicles 32:9 and Isaiah 36:2. The Israelites learn of the departure of the Assyrians from Lachish in II Kings 19:8 and Isaiah 37:8.

The Book of Jeremiah (34:7) lists Lachish as one of the last three fortified cities in Judah to fall to the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II. In the Book of Nehemiah (11:30) Lachish is mentioned as an area where the people of Judah settled during the time of the Achaemenid Empire.

Identification[edit]

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Lachish was identified with Tell el-Hesi from a cuneiform tablet found there (EA 333). The tablet is a letter from an Egyptian official named Paapu, reporting cases of treachery involving a local kinglet, Zimredda. However this hypothesis is no longer accepted. [6] More recent excavations have identified Tell ed-Duweir as Lachish.

Archaeology[edit]

The site of Tell ed-Duweir was first excavated in 4 seasons between 1932 and 1938 by the Wellcome-Marston Archaeological Research Expedition. The work was led initially by James Leslie Starkey until he was murdered by Arab bandits. The effort was completed by Olga Tufnell; publication, identifying seven occupation levels, was completed in 1958.[7][8][9][10] In 1966 and 1968, in a dig which focused mainly on the "Solar Shrine",Yohanan Aharoni worked the site on behalf of Hebrew University and Tel Aviv University.[1][11]

Excavation and restoration work was conducted between 1973 and 1994 by a Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology and Israel Exploration Society team led by David Ussishkin.[12][13][14] The excavation focused on the Late Bronze (1550–1200 BCE) and Iron Age(1200–587 BCE) levels.[1]

Paleo-Hebrew letters on ostraca[edit]

Main article: Lachish letters

Excavation campaigns by James Leslie Starkey recovered a number of Hebrew letters, written on pieces of pottery, so-called ostraca. Eighteen letters were found in 1935 and three more in 1938, all written in Paleo-Hebrew script. They were from the latest occupational level immediately before the Chaldean siege. They then formed the only known corpus of documents in classical Hebrew.[15][16]

LMLK seals[edit]

Another major contribution to Biblical archaeology from excavations at Lachish are the LMLK seals, which were stamped on the handles of a particular form of ancient storage jar. More of these artifacts were found at this site (over 400; Ussishkin, 2004, pp. 2151–9) than any other place in Israel (Jerusalem remains in second place with more than 300). Most of them were collected from the surface during Starkey's excavations, but others were found in Level 1 (Persian and Greek era), Level 2 (period precedingBabylonian conquest by Nebuchadnezzar), and Level 3 (period preceding Assyrian conquest by Sennacherib). It is thanks to the work of David Ussishkin's team that eight of these stamped jars were restored, thereby demonstrating lack of relevance between the jar volumes (which deviated as much as 5 gallons or 12 litres), and also proving their relation to the reign of Biblical king Hezekiah.[17][18]

The 1898 Reference by Bliss, contains numerous drawings, including examples of Phoenician, etc. pottery, and items from pharaonic Egypt, and other Mediterranean, and inland regions.

The Fourth Expedition to Lachish[edit]

In 2013, a fourth expedition to Lachish was begun under the direction of Yosef Garfinkel, Michael G. Hasel, and Martin G. Klingbeil to investigate the Iron Age history of the site on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the Institute of Archaeology, Southern Adventist University. Other consortium institutions include Virginia Commonwealth University, Oakland University and Korean Jangsin University.[19][20][21][22]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i King, Philip J. (August 2005). "Why Lachish Matters". Biblical Archaeology Review 31 (4). Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ Lachish

- ^ David Ussishkin, The conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib, Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology, 1982, ISBN 965-266-001-9

- ^ William H. Shea, Sennacherib's Description of Lachish and of its Conquest, Andrews University Seminary Studies, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 171-180, 1988

- ^ Samuel, Rocca (2012). The Fortifications of Ancient Israel and Judah 1200–586 BC. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9781782005216.

- ^ Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, Tell el Hesy (Lachish), Published for the Committee of the Palestine exploration fund by A. P. Watt, 1891

- ^ J.L. Starkey et al., Lachish I (Tell ed Duweir): Lachish Letters Oxford University Press, 1938

- ^ Olga Tufnell et. al, Lachish II., (Tell ed Duweir). The Fosse Temple, Oxford University Press, 1940

- ^ Olga Tufnell, Lachish (Tell ed-Duweir) III: The Iron Age. The Wellcome-Marston Archaeological Research Expedition to the Near East. Text and Plates Volumes, Oxford University Press, 1953

- ^ Olga Tufnell, Lachish (Tell el Duweir) IV : The Bronze Age, Published for the Trustees of the late Sir Henry Wellcome by the Oxford University Press, 1958.

- ^ Yohanan Aharoni, Investigations at Lachish: The sanctuary and the residency (Lachish V), Gateway Publishers, 1975, ISBN 0-914594-02-8

- ^ D. Ussishkin, Excavations at Tel Lachish - 1973–1977, Preliminary Report, Tel Aviv, vol. 5, pp. 1-97, 1978

- ^ D. Ussishkin, Excavations at Tel Lachish 1978–1983: Second Preliminary Report, Tel Aviv, vol. 10, pp. 97-175, 1983

- ^ D. Ussishkin, Excavations and Restoration Work at Tel Lachish: 1985–1994, Third Preliminary Report, Tel Aviv, vol. 23, pp. 3-60, 1996

- ^ W. F. Albright, The Oldest Hebrew Letters: The Lachish Ostraca, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 70, pp. 11-1, 1938

- ^ W. F. Albright, A Reëxamination of the Lachish Letters, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 73, pp. 16-21, 1939

- ^ D. Ussishkin, Royal Judean Storage Jars and Private Seal Impressions, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, vol. 223, pp. 1-13, 1976

- ^ D. Ussishkin, The Destruction of Lachish by Sennacherib and the Dating of the Royal Judean Storage Jars, Tel Aviv, vol. 4, pp. 28-60, 1977

- ^ http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-sites-places/biblical-archaeology-sites/khirbet-qeiyafa-and-tel-lachish-excavations-explore-early-kingdom-of-judah

- ^ http://www1.southern.edu/lachish/reports-and-publications/publications.html

- ^ http://members.bib-arch.org/publication.asp?PubID=BSBA&Volume=39&Issue=6&ArticleID=3

- ^ http://www.kukmindaily.co.kr/article/view.asp?page=&gCode=7111&arcid=0009707875&code=71111101

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Barnett, R. D. "The Siege of Lachish." Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 8, pp. 161–164, 1958

- Bliss, Frederick. Numerous artifact drawings, also "Layer by Layer" drawings of Tell el-Hesy. Also an original attempt of the only el Amarna letter found at site, Amarna Letters, EA 333. A Mound of Many Cities; or Tell El Hesy Excavated, by Frederick Jones Bliss, PhD., explorer to the Fund, 2nd Edition, Revised. (The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.) c 1898.

- Grena, G.M. (2004). LMLK--A Mystery Belonging to the King vol. 1. Redondo Beach, California: 4000 Years of Writing History. ISBN 0-9748786-0-X.

- Lawrence T. Geraty, Archaeology and the Bible at Hezekiah's Lachish, Andrews University Seminary Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 27–37, 1987

- Magrill, Pamela, A researcher's guide to the Lachish collection in the British Museum, 2006, British Museum Research Publication 161, ISBN 0861591615, fully available online

- Arlene M. Rosen, Environmental Change and Settlement at Tel Lachish Israel, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 263, pp. 55–60, 1986

- D. Ussishkin, The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994), Volumes I-V, Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology vol. 22, Tel Aviv University, 2004, ISBN 9652660175

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tel Lachish. |

Zedekiah

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Rulers of Judah |

|---|

Zedekiah (/ˌzɛdᵻˈkaɪə/; Hebrew: צִדְקִיָּהוּ, Modern Tsidkiyyahu, Tiberian Ṣiḏqiyyā́hû ; "My righteousness is Yahweh"; Greek: Ζεδεκίας, Zedekías; Latin: Sedecias), also writtenTzidkiyahu, was a biblical character, the last king of Judah before the destruction of the kingdom by Babylon. Zedekiah had been installed as king of Judah byNebuchadnezzar II, king of Babylon, after a siege of Jerusalem in 597 BCE, to succeed his nephew, Jeconiah, who was overthrown as king after a reign of only three months and ten days.

William F. Albright dates the start of Zedekiah's reign to 598 BCE, while E. R. Thiele gives the start in 597 BCE.[1] On that reckoning, Zedekiah was born in c. 617 BCE or 618 BCE, being twenty-one on becoming king. Zedekiah's reign ended with the siege and fall of Jerusalem to Nebuchadnezzar II, which both Albright and Thiele agree took place in 586 BCE, though other scholars assert that Jerusalem fell in 587 BCE.[citation needed]

The prophet Jeremiah was his counselor, yet he did not heed the prophet and his epitaph is "he did evil in the sight of the Lord". (2 Kings 24:19-20; Jeremiah 52:2-3)

Contents

[hide]Background[edit]

When Babylon rose against Assyria it caused upheavals that led to the destruction of Judah. Egypt concerned about the new threat, moved northward to support Assyria. It set on the march in 608, moving via Judah. King Josiah, attempted to block the Egyptian forces, and fell mortally wounded in battle at Megiddo. Josiah's younger son Jehoahaz was chosen to succeed his father to the throne. Three months later the Egyptian pharaoh Necho, returning from the north, deposed Jehoahaz in favor of his older brother, Jehoiakim. Jehoahaz was taken back to Egypt as a captive.[2]

After the Egyptians were defeated by the Babylonians at the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II then besieged Jerusalem. Jehoiakim changed allegiances to avoid the destruction of Jerusalem. He paid tribute from the treasury, some temple artifacts, and some of the royal family and nobility as hostages. The subsequent failure of the Babylonian invasion into Egypt undermined Babylonian control of the area, and after three years, Jehoiakim switched allegiance back to the Egyptians and ceased paying the tribute to Babylon. In 599 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II invaded Judah and again laid siege to Jerusalem. In 598 BCE, Jehoiakim died during the siege and was succeeded by his son Jeconiah (also known as Jehoiachin). Jerusalem fell within three months. Jeconiah was deposed by Nebuchadnezzar, who installed Zedekiah, Jehoiakim's brother, in his place.

Life and Reign[edit]

According to the Hebrew Bible, Zedekiah was made king of Judah by Nebuchadnezzar II in 597 BCE at the age of twenty-one. This is in agreement with a Babylonian chronicle, which states, "The seventh year: In the month Kislev the king of Akkad mustered his army and marched to Hattu. He encamped against the city of Judah and on the second day of the month Adar he captured the city (and) seized (its) king. A king of his own choice he appointed in the city (and) taking the vast tribute he brought it into Babylon."[3]

The kingdom was at that time tributary to Nebuchadnezzar II. Despite the strong remonstrances of Jeremiah, Baruch ben Neriah and his other family and advisors, as well as the example of Jehoiakim, he revolted against Babylon, and entered into an alliance with Pharaoh Hophra of Egypt. Nebuchadnezzar responded by invading Judah. (2 Kings 25:1). Nebuchadnezzar began a siege of Jerusalem in December 589 BC. During this siege, which lasted about thirty months,[4] "every worst woe befell the city, which drank the cup of God's fury to the dregs". (2 Kings 25:3; Lamentations 4:4, 5, 9)

At the end of his eleven year reign, Nebuchadnezzar succeeded in capturing Jerusalem. Zedekiah and his followers attempted to escape, making their way out of the city, but were captured on the plains of Jericho, and were taken to Riblah.

There, after seeing his sons put to death, his own eyes were put out, and, being loaded with chains, he was carried captive to Babylon (2 Kings 25:1-7; 2 Chronicles 36:12;Jeremiah 32:4,-5; 34:2-3; 39:1-7; 52:4-11; Ezekiel 12:13), where he remained a prisoner until he died.

After the fall of Jerusalem, Nebuzaradan was sent to destroy it. The city was plundered and razed to the ground. Solomon's Temple was destroyed. Only a small number of vinedressers and husbandmen were permitted to remain in the land. (Jeremiah 52:16)

Epilogue[edit]

Gedaliah, with a Chaldean guard stationed at Mizpah, was made governor to rule over the remnant of Judah, the Yehud Province. (2 Kings 25:22-24, Jeremiah 40:6-8) On hearing this news, all the Jews that were in Moab, Ammon, Edom, and in other countries returned to Judah. (Jeremiah 40:11-12) However, before long Gedaliah was assassinated, and the population that was left in the land and those that had returned fled to Egypt for safety. (2 Kings 25:26, Jeremiah 43:5-7) In Egypt, they settled in Migdol, Tahpanhes, Noph, and Pathros. (Jeremiah 44:1)

Chronological notes[edit]

The Babylonian Chronicles give 2 Adar (16 March), 597 BCE, as the date that Nebuchadnezzar captured Jerusalem, thus putting an end to the reign ofJehoaichin.[5] Zedekiah's installation as king by Nebuchadnezzar can therefore be firmly dated to the early spring of 597 BCE. Historically there has been considerable controversy over the date when Jerusalem was captured the second time and Zedekiah's reign came to an end. There is no dispute about the month: it was the summer month of Tammuz (Jeremiah 52:6). The problem has been to determine the year. It was noted above that Albright preferred 587 BCE and Thiele advocated 586 BCE, and this division among scholars has persisted until the present time. If Zedekiah's years are by accession counting, whereby the year he came to the throne was considered his "zero" year and his first full year in office, 597/596, was counted as year one, Zedekiah's eleventh year, the year the city fell, would be 587/586. Since Judean regnal years were measured from Tishri in the fall, this would place the end of his reign and the capture of the city in the summer of 586 BCE. Accession counting was the rule for most, but not all, of the kings of Judah, whereas "non-accession" counting was the rule for most, but not all, of the kings of Israel.[1][6]

The publication of the Babylonian Chronicles in 1956, however, gave evidence that the years of Zedekiah were measured in a non-accession sense. This reckoning makes year 598/597 BCE, the year Zedekiah was installed by Nebuchadnezzar according to Judah's Tishri-based calendar, to be year "one," so that the fall of Jerusalem in his eleventh year would have been in year 588/587 BCE, i.e. in the summer of 587 BCE. The Bablyonian Chronicles allow the fairly precise dating of the capture of Jehoiachin and the start of Zedekiah's reign, and they also give the accession year of Nebuchadnezzar's successor Amel-Marduk (Evil Merodach) as 562/561 BCE, which was the 37th year of Jehoiachin's captivity according to 2 Kings 25:27. These Babylonian records related to Jehoiachin's reign are consistent with the fall of the city in 587 but not in 586, as explained in the Jehoiachin/Jeconiah article, thus vindicating Albright's date. Nevertheless, scholars who assume that Zedekiah's reign should be calculated by accession reckoning will continue to adhere to the 586 date, and so the infobox contains this as an alternative.

Genealogical note[edit]

Zedekiah was the third son of Josiah, and his mother was Hamutal the daughter of Jeremiah of Libnah, thus he was the brother of Jehoahaz (2 Kings 23:31, 24:17-18, 23:31, 24:17-18).

His original name was Mattanyahu (Hebrew: מַתַּנְיָהוּ, Mattanyāhû, "Gift of God"; Greek: Μαθθανιας; Latin: Matthanias; traditional English: Mattaniah), but when Nebuchadnezzar II placed him on the throne as the successor to Jehoiachin, he changed his name to Zedekiah (2 Kings 24:17).

In the Book of Mormon[edit]

According to the Book of Mormon, Zedekiah's son Mulek escaped death and traveled across the ocean to the Americas, where he founded a nation that later merged with another Israelite splinter group, theNephites.[7][8]

Zedekiah

| ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jeconiah | King of Judah 597 – 587 or 586 BCE | Judah conquered by Nebuchadnezzar II ofBabylon |

| Leader of the House of David | Succeeded by Shealtiel | |

See also[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zedekiah. |

- Jeconiah/Jehoiachin for more complete discussion of 587 vs. 586

- Zedekiah's Cave

- List of minor Biblical figures: Zidkijah

References[edit]

- ^ a b Edwin Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951; 2d ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965; 3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983). ISBN 0-8254-3825-X, 9780825438257, 217.

- ^ Bakon, Shimon. "Zedekiah: Last King of Judah", Jewish Bible Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2008

- ^ Readings from the Ancient Near East: Primary Sources for Old Testament Study. Baker Academic. p. 159. ISBN 978-0801022920.

- ^ Knight, Doug and Amy-Jill Levine (2011). The Meaning of the Bible. New York City: HarperOne. p. 31. ISBN 9780062067739.

- ^ D. J. Wiseman, Chronicles of Chaldean Kings in the British Museum (London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1956) 73.

- ^ Leslie McFall, “A Translation Guide to the Chronological Data in Kings and Chronicles,” Bibliotheca Sacra 148 (1991) 45.[1][dead link]

- ^ Helaman 6:10

- ^ Helaman 8:21

The Name of God http://lavia.org/EN_Name.html

The Oldest Hebrew Letters: The Lachish Ostraca http://www.jstor.org/stable/1354816?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

“The Prophet” in the Lachish Ostraca http://biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/tp/lachish_thomas.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment